Ends and Pieces: "The Link of Belonging"

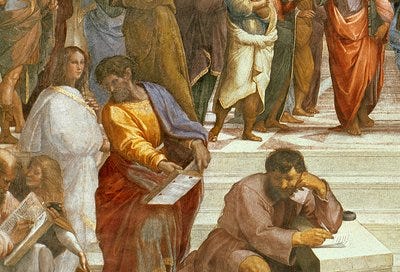

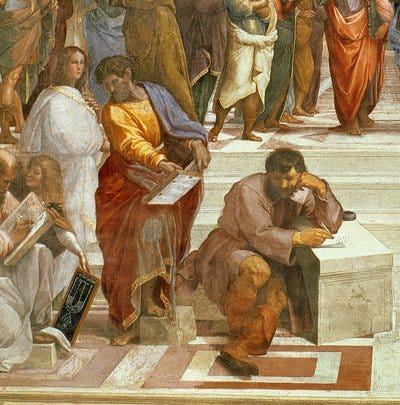

Scholar and student as members of "the society of neighbors" through the intellect and imagination

“Ends and Pieces” is an occasional series which came from the struggle to try and keep my posts to a reasonable length while also wanting to quote an author's entire context, which - of course - increases the length of the piece as I’m simultaneously trying to whittle it down. I decided to do what those geniuses in the bacon industry have done, and gather up all the delicious ends and pieces - those hunks of salty, smoky deliciousness that are not quite uniform enough to sell as “Bacon Proper” - and plop them down here. Too misshapen to be a proper post, but too good to throw out. I’ll always title the post as “Ends and Pieces” and give the subtitle over to descriptors so you can see if it’s worth your time.

The scholar and the cultivated amateur form a partnership of knowledge. It is a membership, a unity of differences, made through a mutual appreciation and which allows fo

r the exchange of mental energies between the expert and the amateur. This exchange allows knowledge that might become too specialized and isolated to find a place in the shared society of scholar and amateur. In an essay called The Knowledge of Good and Evil, Frye writes about the pursuit of the intellectual virtue of detachment in the sciences and the humanities, and how this detachment is balanced by what Frye calls “the myth of concern” which, he says, “includes the sense of the importance of preserving the integrity of the total human community.”

The quote is long and in-depth. You could even say its esoteric. But I think it is a worthwhile compliment to thr encouragement yesterday to the amateur scholar. We have a place to fill. I am quoting Frye at length because I want to provide the necessary backdrop for the final paragraph to have its full force:

At present it may be said that the principle, which is also a moral principle, that every discipline must be as scientific as its subject matter will allow it to be, or abandon all claim to be taken seriously, is now established everywhere in scholarship. … The permeation of ordinary scholarly life by the same virtue is marked in the deference paid to impersonality. … It is significant that the personal appropriation of knowledge is not considered the scholar’s social goal. The scholar whose social behavior reflects his knowledge too obtrusively is a pedant, and the pedant, whatever the degree of his scholarship, is regarded as imperfectly educated.

Yet there is a widespread popular feeling, expressed in many clichés, that the pedant, the scholar who does not accurately sense the relation between scholarship and ordinary life, is in fact typical of the university and its social attitude. The forward impetus of the scientific spirit backfires in the public relations department: the disinterested pursuit of knowledge acquires, for its very virtues, the reputation of being unrelated to social realities. The intellectual, it is thought, lives in an over-simplified Euclidean world; his attitude to society is at best aloof, at worst irresponsible. A fair proportion of incoming freshmen…though mildly curious about the scholarly life, are convinced that it is an ‘ivory tower’, and that only a misfit would get permanently trapped in it. I call this popular view a cliché, which it clearly is, but the clichés of social mythology are social facts. And what this particular cliché points to, rightly or wrongly, is the insufficiency of detachment and objectivity as exclusive moral goals. …

Detachment becomes indifference when the scholar ceases to think of himself as participating in the life of society, and of his scholarship as possessing a social context. We see this clearly when we turn from the subject itself to the social use made of it. Psychology is a science, and must be studied with detachment, but it is not a matter of indifference whether it is used for a healing art, or for ‘motivational research’ designed to force people to buy what they neither want nor need, or for propaganda in a police state. …

It seems obvious that concern has nothing directly to do with the content of knowledge, but that it establishes the human context into which the knowledge fits, and to that extent informs it. The language of concern is the language of myth, the total vision of the human situation, human destiny, human inspirations and fears. The mythology of concern reaches us on different levels. On the lowest level is the social mythology acquired from elementary education and from one’s surroundings, the steady rain of assumptions and values and popular proverbs and clichés and suggested stock responses that soaks into our early life and is constantly reinforced, in our day, by the mass media. In this country most elementary teaching is, or is closely connected with, the teaching of ’the American way of life.’ … The beliefs and views are primarily about America, but are extended by analogy to the rest of the human race. Such social mythology expresses a concern for society, both immediate and total, which may not be very profound or articulate, but which is a mighty social force for all that. Similar social mythologies have been developed in all nations and in all ages…

Above this is a body of general knowledge, mainly in the area of the humanities, which is also assimilated to a body of beliefs and assumptions. This forms the structure of what might be called initiatory education, the learning of what the cultivated and well-informed people in one’s society know, within the common acceptances which give that society its coherence. Initiatory education enters into the university’s liberal arts curriculum and is reinforced by the upper strata of the mass media, ranging from churches to the more literary magazines. It forms a body of opinion which I call the mythology of concern.

The traditional picture of scholarship as an intensely specialized activity, motivated by detachment and the pursuit of truth for its own sake, is correct as far as it goes. The arts, and the detailed research which is scholarship in this more restricted sense, emerge out of initiatory education like icebergs, with an upper part which is specialized and a lower part which is submerged in the scholar’s general activity as a human being. The mythology of initiatory education is not itself scholarship in the restricted sense, but its upper levels modulate into a scholarly area of great and essential importance. The scholar is involved with this area in three ways: as a teacher, as a popularizer of his own subject, and as an encyclopedist. That is, if he happens to be interested in conspectus or broad synthesizing views, he will spend much or all of his time in articulating and making more coherent his version of his society’s myth of concern. …

The world of scholarship, in the restricted sense, is too specialized and pluralistic to form any kind of over-all society. Each scholar, left purely to his own scholarship, would see the human situation only from his own point of view, and the resulting sectarianism would probably destroy society, as the confusion of tongues led to the abandoning of Babel. Hence the importance of having an area of scholarship intermediate between general information and the pursuit of detailed research. It is essentially an activity of exploring the social roots of knowledge, of maintaining communication among scholars, of formulating the larger views and perspectives that mark the cultivated man, and of relating knowledge to the kind of beliefs and assumptions that unite knowledge with the good life.” (emphasis mine)

(I can't help but mention Charlotte Mason and the science of relations here. There is a relational aspect inherent in real knowledge. Knowledge always connects with other things we are learning.)

But the essay doesn’t end here. Frye is showing that this membership in knowledge is not just an optional perk to add to the good life; it is the good life. The good life must have a social component, and “the force that creates the myth of concern drives it onward from the specific society one is in to larger and larger groups,” until finally there is an “abiding loyalty…to mankind as a whole.”

But, Frye says, this is not the end:

“If this were the whole story, the myth of concern would end simply in a vague and fuzzy humanitarianism. But in proportion as one’s loyalty stretches beyond one’s nation to the whole human race, one’s concrete and specific human relationships become more obvious. A new kind of society appears in the center of the world, a society which is different for every man, but consists of those whom he can see and touch, those whom he influences and by whom he is influenced: a society, in short, of neighbors. Who is our neighbor? We remember that this question was asked of Jesus, who regarded it as a serious question, and told the story of the Good Samaritan to answer it. And, as the alien figure of the Samaritan, in a parable to to Jews makes obvious, one’s neighbor is not necessarily a member of the same social or racial or class group as oneself. One’s neighbor is the person to whom one has been linked by some kind of creative human act, whether of mercy or charity, as in the parable itself; or by the intellect or the imagination, as with the teacher, scholar, or artist; or by love, whether spiritual or sexual. The society of neighbors, in this sense, is our real society; the society of all men, for who we feel tolerance and goodwill rather than love, is in the background. … (emphasis mine)

Frye ends the essay with this:

“Throughout civilization there runs a tendency known in the Orient as ‘making oneself small’, of being modest and deprecating about one’s own abilities, and being much more ready to concede the abilities of others. Some of this is self-protective hypocrisy, but not all of it is. When we think about our own identity, we tend at first to think of it as something buried beneath what everyone else sees, something that only we can reach in our most solitary moments. But perhaps, for ordinary purposes at least, we may be looking for our identity in the wrong direction. To identify something is first of all to put it in the category of things to which it belongs: the first step in identity is the realization humanus sum. We belong to something before we are anything, nor does growing in being diminish the link of belonging. Granted a reasonably well disposed and unenvious community, perhaps our reputation and influence, what others are willing to think that we are, comes nearer our being our real selves than anything stowed away inside us… In the society that the mythology of concern ultimately visualizes, a man’s real self would consist of primarily of what he creates and of what he offers. The scholar as man has all the moral dilemmas and confusions of other men, perhaps intensified by the particular kind of awareness that his calling gives him. But qua scholar what he is is what he offers to his society, which is his scholarship. If he understands both the worth of the gift and the worth of what it is given for, he needs, so far as he is a scholar, no other moral guide.”

For the cultivated amateur, we offer the scholar a place, a home for the scholar and his gift - his detailed knowledge and in-depth research. We join him in his enjoyment of his subject, we wonder along side him and love hearing him expound in detail what we can sense and see in general. We accompany him on his search for a social application of all his knowledge. We make a home for it in us, and through us it makes its way out into the larger world. It is no small thing to be a cultivated and cultivating amateur, to be a member of a “real society,” a “society of neighbors” linked together by the creative human acts of intellect, imagination, and love.